The divide between those inside the academy and those outside of it appears to be as big as ever, and it is continuing to widen. Those inside feel they do a good job at managing their finances in an ever-changing economy, and that the primary issue is a lack of sufficient public support. Those outside don’t trust the academy’s management of public funds.

Undoubtedly, this lack of trust is – to some extent – based on personal observations of inefficiency and ineffectiveness. Even those of us who went to college back when remember waiting lists for courses we needed, long lines for seats we were lucky enough to get in core courses, under-filled classes taught by senior faculty, huge classes taught by grad assistants with a limited grasp of English, and processes that felt more arbitrary than student-friendly. It was fun and incredibly valuable, but hardly a model of institutional effectiveness. Those us who are parents get to confirm, up close and personal, that little has changed.

Everyone agrees that cost is a major issue. A big part of the cost discussion is, justifiably, focused on administration where most of the job growth has come. My focus in this article, however, is on the roughly 58% of the core operating budget that goes to academic resources – instructors and academic space. Academic resources are still the biggest and most important part of the budget at academic institutions. How well are they managed?

To answer that question, let’s not just look at data. Let’s also compare higher education to another industry engaged in a similarly complex resource allocation exercise. The best comparison that I could muster is the airline industry. Both higher education and the airlines must deal with thousands of customers with diverse, changing needs. Both must allocate fixed resources while facing extreme pressure to keep prices under control. Both have large financial variables materially out of their control – higher education: subsidy, airlines: fuel costs.

I have spent my career working with colleges and universities to improve the effectiveness with which they allocate instructors and academic space. We are making progress at many institutions, but the more common process of scheduling these resources still bears little resemblance to that used by the airlines to schedule its flights (and their flight crews and planes). What could colleges and universities learn from the airlines?

First, that the customer needs must be the priority. While we’ve all been frustrated by travel delays, most airline (especially my favorite, Southwest Airlines) spend a lot of energy understanding and responding to our needs. Can you imagine if an airline, instead of prioritizing our needs, allowed its pilots to determine where and when to fly? What if a small group of pilots could call “dibs” on their favorite plane and not share it with others? What if the pilots based in each city the airline served made all of these decisions without talking to the other bases to ensure passengers could make their connections? What if they didn’t have to file their flight plans for approval with air traffic control?

Essentially, this is what happens in most academic units at most colleges and universities. The faculty members commonly decide what to teach and when/where to teach it. To minimize change, these decisions are rolled forward from Fall-to-Fall and Spring-to-Spring with very little information about changing student course needs. Each academic unit prepares their little piece of the schedule without collaborating with other units or the Provost’s office (air traffic control). The result is student frustration that leads to retention and completion problems. In fact, students rank their experience at registration as their #1 challenge each year in the Noel-Levitz Survey on Student Satisfaction.

Next, we could learn that a customer-friendly approach is a resource-efficient approach. When the customer is the most important consideration, limited resources are aligned with their needs. The fact is that higher education is much less efficient than the airlines. This is true despite two significant advantages we have over the airlines stemming from our students’ pursuit of a credential – we know where our customers need to go next, and we have more “control” of them to continue on with us.

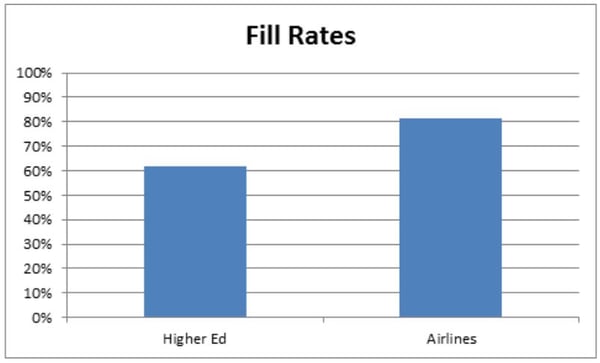

Higher education classes are only filled about 75%, on average, and only 62% of a typical classroom seats are occupied. By comparison, according to IATA Economics, airlines are projected to average an 81.3% fill rate for an average flight in 2014.

Higher education leaders would be well served to turn their energy away from complaining about a lack of support from their states and toward rebuilding trust in their ability to meet students’ needs and be good stewards of state appropriations. This could start with improving their allocation of critical academic resources. We could learn something from the airlines.